Background

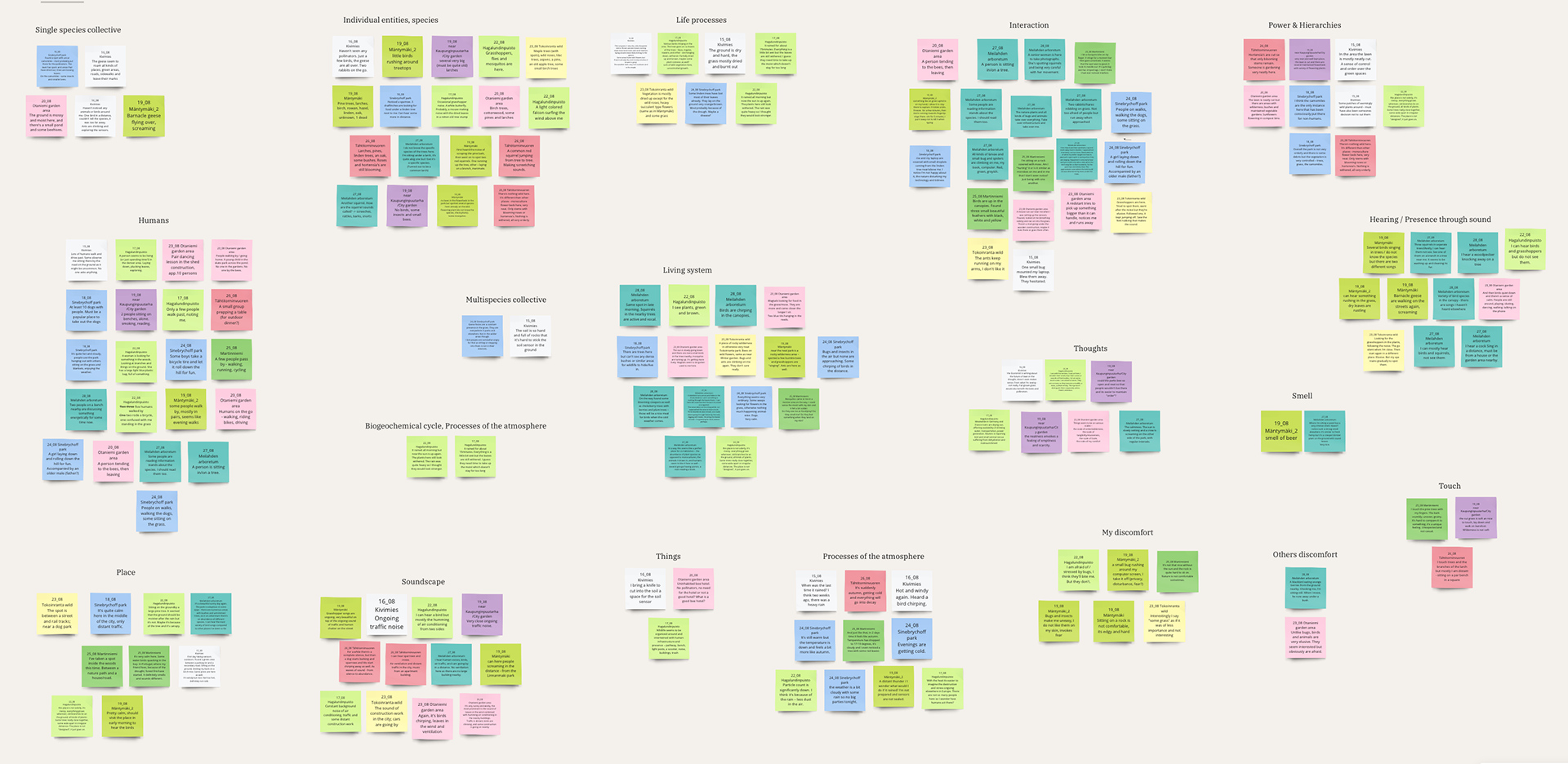

The planet and the lives of humans are accompanied, shaped, and defined by things and design. Human existence and being in the world are seen as relational – shaped by things, technology, and materiality. The more-than-human-centred approach to design explores not only the human experience but also that of nonhuman stakeholders opening up the design space to include agents of various species and forms.

The planet and the lives of humans are accompanied, shaped, and defined by things and design. Human existence and being in the world are seen as relational – shaped by things, technology, and materiality. The more-than-human-centred approach to design explores not only the human experience but also that of nonhuman stakeholders opening up the design space to include agents of various species and forms.

The inclusion of natural nonhuman stakeholders brings the interaction design practice outdoors where lately, it is being recognised that urban wildlife, plants, insects, and other nonhuman species inhabit cities alongside humans and should be acknowledged in urban planning and design (Houston et al. 2018; Smith, Bardzell, and Bardzell 2017). Cities and urban settlements house over half of humanity (World Bank 2023) and play a prominent role in climate change. Major emitters of greenhouse gases, with more than 60 per cent of greenhouse gases originating from urban areas, cities are also prone to more pollution and accumulation of heat (Gaulkin 2022; United Nations n.d.). On the other hand, nature-based solutions are being implemented in the development of urban areas, signalling tactics of adaptation and resilience (Magdelenat et al. 2021). Cities, therefore, are seen as shared spaces with grey, green and blue infrastructure where humans and all kinds of nonhumans cohabit and co-create realities.

Goals

Propogate attentiveness towards unshielded and everchanging outdoor realities considering nonhuman inhabitants. Encourage care in urban multispecies communities. Create connections in a shared time and space. Create a product for a vision that includes and values nonhuman stakeholders in shared urban realities.

Opportunity

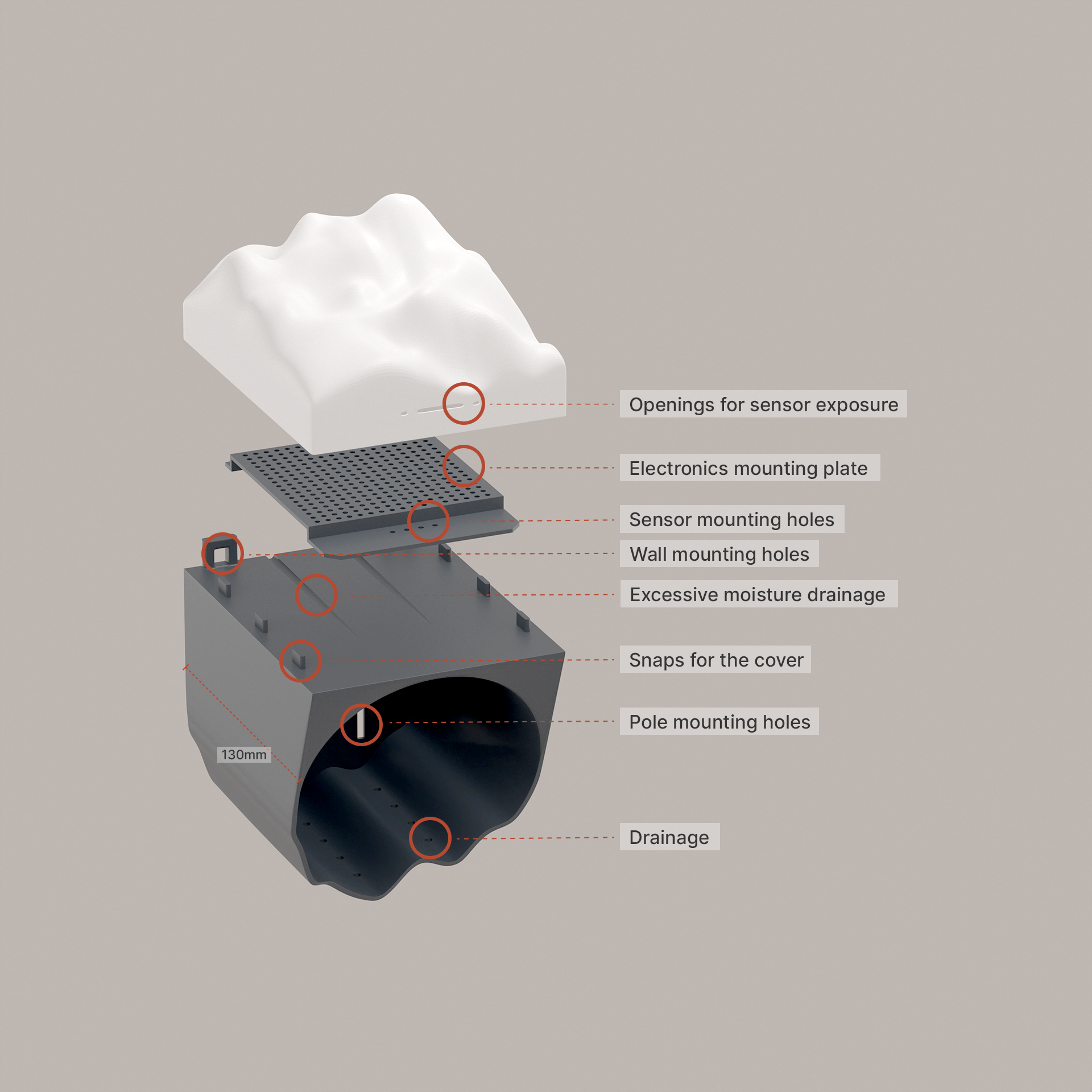

During the discovery phase, I noticed fewer pollinators in groomed and maintained city parks than in urban wild zones. To my inexpert eye, it seemed to suggest that the lack of wild plants, natural vegetation and uninterrupted life processes seemed to drive the pollinators to forage and nest in wilder areas. According to Ayers and Rehan, due to their heterogeneity, cities often display a higher degree of biodiversity than other areas, however, local features are crucial to pollinators, and urban green spaces can be optimized for pollinator habitation by reducing management intensity, increasing native floral richness, and promoting green patch connectedness to ensure pollinator movement (Ayers and Rehan 2021). Pollinators are often regarded as the protectors of plant biodiversity and food security, and the urban green zones can be adapted to more suitable habitats for various species. Overall, due to the lack of bare ground and the presence of novel nesting opportunities such as cracks in various structures as well as insect hotels in some cases, urban spaces attract more cavity-nesting than ground-nesting bees that also tend to be small-bodied late emerging species (Ayers and Rehan 2021). Urban green spaces are often maintained, groomed and managed, thus reducing nesting opportunities. While it might be argued that in-action, e.g. non-management and development of urban wild zones, could be the most successful strategy, I decided to create a bee hotel that would serve as a light piece at the same time, proposing a possibility of creating interactive objects that serve both nonhumans and humans.

Outcome

The whole research and prototyping process has allowed to gather more understanding of the more-than-human-centred design process. The knowledge can be summarised in a list of considerations that can be taken into account when designing for more-than-human cohabitation in shared spaces. The proposed considerations are:

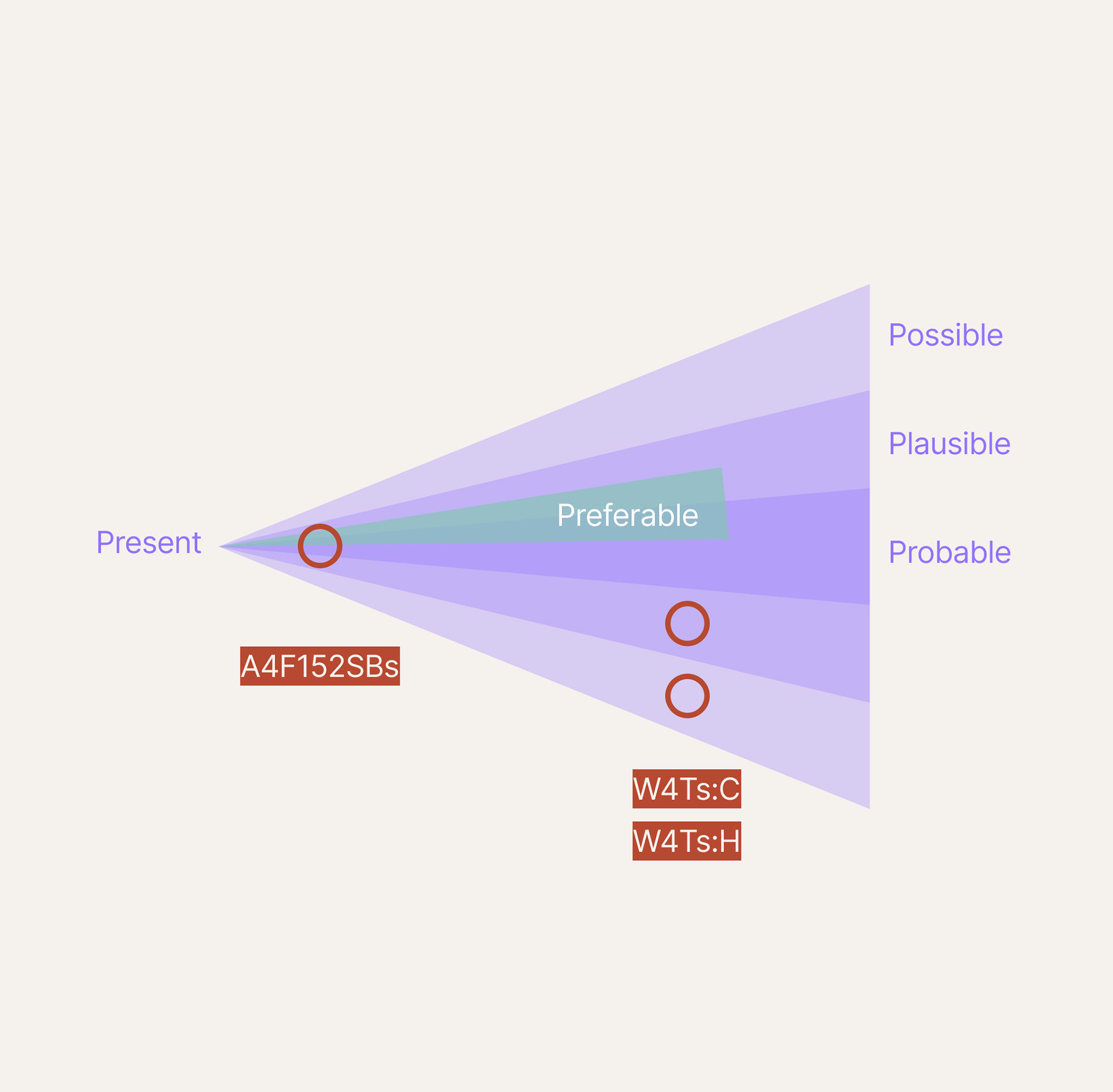

– What are the features of the preferred future, and what scenarios does the design consider?

– What are the environmental characteristics of the anticipated space, and what possible future risks do they contain?

– What nonhuman stakeholders are involved, and what could be the ways or tactics to approach them to gain knowledge?

– What techniques could be used for noticing, gathering, and storing multisensory data?

– Who does the knowing/designing, and what are the advantages and limitations it poses?

– What are the possible discomforts and risks to be encountered, and how to avoid them?

– What could be the tactics to increase the level of nonhuman collaboration during research, design and testing?

– In what ways should time and season be considered?

– What are the roles of humans, and how can human knowledge or experience be beneficial?